Goal Setting

Four students—Connor, Emily, Freddy, and Anna—all attend the same school and have recently entered their sophomore year. They all begin the year in a rough spot, receiving C’s on most of their classes for the first quarter. But, by the end of the year, only one of them—Anna—has successfully turned it around, ending her fourth quarter with all A’s.

Major performance gaps that emerge between students with similar circumstances and skill levels usually stem from their differences in work ethic. One major factor of work ethic leads to the kind of growth depicted in Anna’s story: goal setting.

What MAKES Anna Different?

Good goal setting increases motivation and inspires students to improve. It raises self-esteem, lowers stress, and encourages better time management. Despite these benefits, many students fail to set goals or set bad goals. Return, for a moment, to our four students and their experience throughout the year:

Conner made no improvements. Unsurprisingly, he set no goals to improve.

Emily finished the year with a B average. Her parents pressured her to earn A’s so that she could get into a “good college”. While she wanted to do better, the pressure stressed her out and kept her from major improvement.

Freddy did very well on a few major assignment, but ended the year with a C average. His parents always told him to “do his best.” Sometimes he did, but most of the time, he remained apathetic and put in the minimum amount of work.

Anna, unlike the others, saw incremental progress. She received B’s in the second and third quarters and ended the year with all A’s. She gave herself specific markers for improvement (an 85 on the next math test, an A- on the science quiz) and kept setting higher goals as she grew in ability.

Most parents know intuitively to avoid Conner’s situation (no goals at all). But few know where to go from there.

Many try to avoid stressing their children out by setting “do your best” goals—i.e. “Just try your hardest on the next history test.” As we saw with Freddy, while “do your best” goals sometimes work for complicated tasks or worried students, they fail to bring about long-term progress.

Plan for Success

Goal setting theory recommends setting a high-achievement, specific goal—for example, “Get an A on the upcoming English essay.” But sometimes, difficult goals lead to student burnout, as with Emily. (Learn more about creating well-structured goals under the organizational support portion of our Covid Learning Loss article)

Recently, some researchers have identified a theory of goal setting that aims at high achievement and freedom of stress. The theory, personal best goal setting, aims at goals that are “optimally challenging”—not too easy, not too difficult. The student’s personal best (their current skill level or average grade) serves as the foundation on which goals are built. Step by step, the goals increase in difficulty with the student’s confidence.

Consider Anna again. We know her baseline—C’s across the board. We also know she wants to improve. Anna and her parents identify four premises for good personal-best goal setting:

Do not immediately shoot for all A’s. This is more likely to stress Anna out than help her improve.

Start with smaller goals. For example, Anna decides to aim for a C+ average on her assignments of the first week of quarter two.

Break the goals down. The more specific the goal, the easier Anna will be able to figure out what she needs to do and assess her progress. So, for example, Anna decides that she wants a B+ quiz average in science for quarter 2. If she gets a C on the first quiz, she knows she needs to change her learning strategy or effort level for the next one.

Reflect on performance and assess confidence levels. Every week or two, Anna and her parents have a conversation about what went well and what could go better over the next couple of weeks. In areas where she succeeded, they set incrementally higher goals, which give her the confidence and drive to pursue more of these little wins. In areas where she fell short, they reduce the goal slightly to make it more achievable. As time goes on, Anna learns which tasks take more work and which she can do easily.

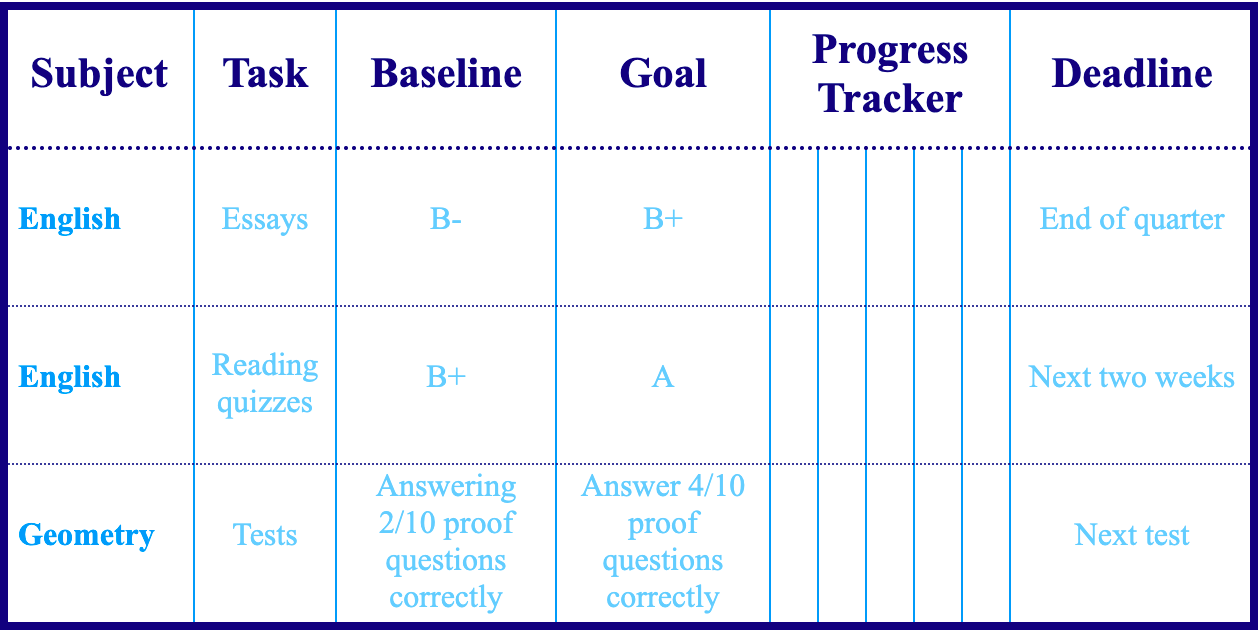

A simple table helps Anna and her parents keep track of goals for multiple subjects at a time. For example:

Work ethic is multifaceted; sometimes, goal setting generates motivation, while sometimes motivation generates goals. As you adapt a strategy for your child, you might find that your child seems apathetic or resistant to improvement. If so, you might want to consult one of our articles on motivation and then come back to this one.