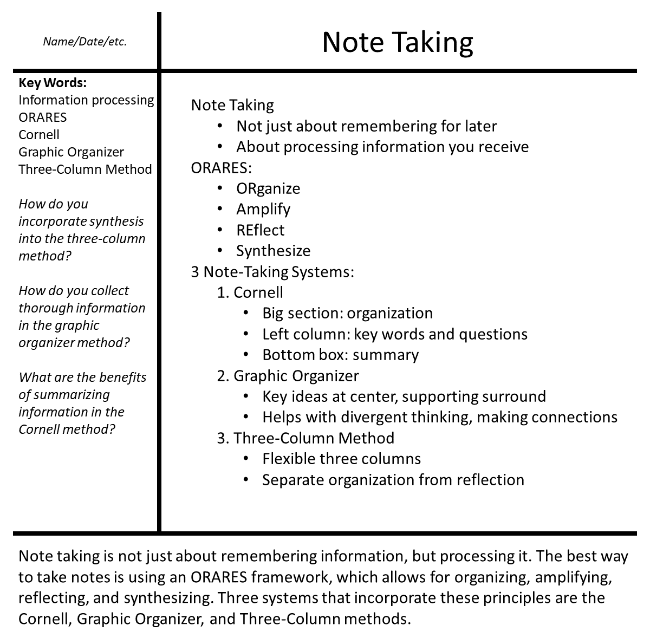

Note Taking

When most people think about note taking in school, they view it as a simple activity: write down what the teacher says and maybe read back over it later. Teachers demand students take notes and parents encourage the practice, but many students would rather just sit in class without this extra step. “Why should I take notes?” they might say. After all, they can find the information on Google or in the handout from the teacher.

This is a reasonable point—in the information age, students possess unlimited access to unlimited information. They do not need a sloppily written copy of the same information available on the internet. However, they do need help processing the information they receive.

Especially in high school (and even more so in college), students do not just regurgitate information from their teachers—they make connections, research their own topics, and craft persuasive viewpoints. This more difficult type of learning requires a higher-power form of note taking: one that not only consumes information, but also digests it.

One group of researchers has developed an acronym that encapsulates the four purposes of effective note taking: ORARES. The ORARES framework requires students to…

ORganize the information (bullet points, subheadings, details and central ideas, etc.)

Amplify the important parts and dispose of the unimportant ones

REflect on their own questions and confusions

Synthesize information learned in the class

Notice that these purposes reject straightforward, word-for-word copying of class information. Instead, they require higher-level thinking and reflection about the course material. Unfortunately, most students write either too little (a few disjointed bullet points on a mostly-blank page) or too much (large paragraphs of unfiltered copying from the teacher). The following structures challenge students to copy less, create more, and begin thinking about what they are learning.

Three Note Taking Systems

Cornell Notes

Cornell notes rely on a three-section system that walks a student through the ORARES framework. The largest box has space for organizing information—collecting the most important details from a class and arranging them well. Then, in the left-hand column, students amplify and reflect by collecting key words (important ideas, vocabulary, formulas, etc.) from the larger box and asking critical questions. In the bottom box, students synthesize the information by writing a short summary of everything on the page—ideally incorporating all the key words from the left-hand column.

Graphic Organizer

Graphic organizers can take many forms, but the most common one is a mind-map. A mind map organizes and amplifies information by setting key ideas at the center of webs and surrounding them with supporting details. It allows for reflection and synthesis by incentivizing a more creative style of thinking. Students who dislike bullet points and subheadings might prefer the graphic organizer format.

Three-Column Method

The three-column method simply requires students to set up three sections, each with a different purpose. The most basic structure includes columns for main ideas (amplification), details (organization), and thoughts/questions (reflection and synthesis). The exact nature of the columns can change depending on the class. For example, in math, the student can use column one for formulas, column two for example problems, and column three for questions. Or in social studies, they could record the timeline, then the details, then a retelling of the story in their own words. For science or literature, they can record main ideas, details, and personal observations.

Implementation

As you encourage your child to experiment with note-taking systems, give them freedom to decide. This flexibility will help them buy into the system. Additionally, encourage them to color-code their notes and write them by hand. Both of these practices make the information more visually memorable and add another layer of in-the-moment processing.

With any habit, begin by starting small. If your child rarely or never takes notes, begin by having them take notes in only one class. If they regularly take notes but lack a clear structure or feel like the notes do not help them, begin by adding one element of structure to all their notes—perhaps the summary section from the Cornell notes or an additional column from three-column notes. As their retention and comprehension improve, your child will grow more willing to continue implementing these structures.